As mentioned in the previous episode, jazz had a big influence on musicians in Ghana. Performers like E.T. Mensah played it in Accra when the Allied troops were stationed there, as well as in London’s Piccadilly clubs. The king of highlife was about to be very happy: the king of jazz was coming! And it was with “All for you”, a song by Mensah, that the great Satchmo was welcomed when he landed in Accra with his wife Lucille.

Listen to the Ghana Freedom Playlist (Spotify, Deezer, YouTube)

This song is actually a cover of the Sly Mongoose theme that Charlie Parker, Armstrong and many others played. It comes from a Creole tune that originated in Louisiana and, before Louisiana, somewhere in the Caribbean. By the time Mensah played the theme it had made a great journey from the Caribbean to the United States and back to Africa. Something of a return to sender.

It was Mensah’s version, played by thirteen bands, that welcomed Armstrong on the tarmac at Accra airport. But instead of the refrain “All for you, E.T., all for you”, they sang “All for you, Louis, all for you”.

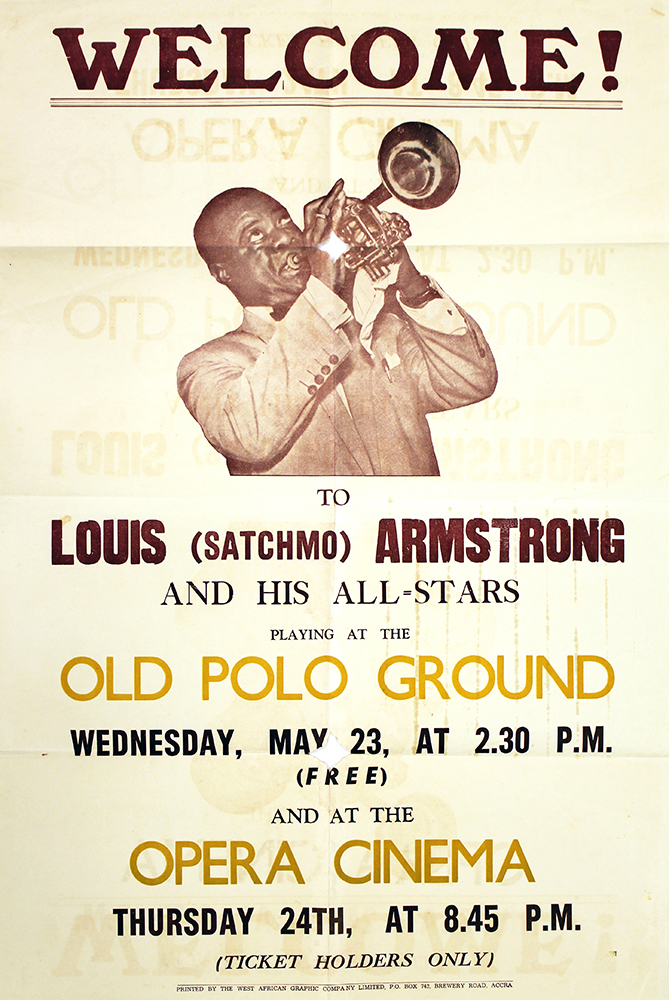

On the tarmac, Armstrong took out his trumpet and accompanied the dozens of brass players to the cars that would take them to the old polo ground, the same one where, almost a year later, Nkrumah would proclaim independence. Between 70 and 100 thousand people gathered, according to the police. What followed was a frenzied jam session, where Armstrong let rip, getting the Ghanaian bigwigs in their traditional dress, and the Ghanaian women all dressed up to the nines, up and dancing. It was an incredible sight, reminding us that jazz and Africa are indeed in the same family.

The next day, Armstrong played at the Paramount Club with E.T. Mensah. In the evening, he performed with his musicians at the Opera Cinema, a concert attended by Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah. Armstrong dedicated the song “Black and Blue” to him.

“I’m white inside that don’t help my case

‘Cause I can’t hide what is in my face

How would it end, ain’t got a friend

My only sin is in my skin

What did I do to be so black and blue…?“

Before his departure, traditional dancers come to perform for Satchmo and his wife. Among the dancers he was moved to see a lady who looked exactly like his mother, who’d passed away twenty years earlier. From then on he was convinced that his ancestors had come from Ghana, explaining this in a telegram he sent just before flying back to New York.

Armstrong, like many other African-Americans after him, came on a pilgrimage to Ghana, and the country opened its arms to them. Even Kwame Nkrumah’s mentor, the thinker W.E.B. Du Bois and author of The Souls of the Black Folk came.

As for the great Satchmo, it was the State Department and the US Ministry of Foreign Affairs who sponsored his incredible African tour of 1960-61, during which he played in 27 cities on the continent. In the midst of the Cold War, the country that had not yet said farewell to segregation was sending a completely different message to the outside world – and particularly to Africa – and was using Armstrong as its ambassador.

Nine months after Armstrong’s visit to Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah became the first President of an independent Ghana.